This was one of the most effective conversations I’ve had about healthcare policy, and how it will impact my doctors every day. Great discussion, great insights, and I’ll use this tip sheet in my clinics.

– CMIO

Problem

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is the government agency responsible for Medicare and Medicaid, and is easily the largest single payer for healthcare in the United States. When CMS changes their rules about basically anything it has significant impacts on clinicians, patients, and nearly all actors in the healthcare space. In 2020 CMS announced that they would adopt recommendations from the American Medical Association (AMA) regarding how outpatient clinicians document, and in turn bill for, their clinical services.

The general consensus among clinician groups, including the American College of Physicians (ACP), was that the changes should dramatically reduce the burden on clinicians and take some of the mismatch between clinical practice and administrative requirements off the table. ACP wanted to get the word out about these user experience improvements, and ensure that the CMS changes could have a positive impact on the worklives of physicians. Doctors needed to understand the real world impacts of the regulatory changes and be inspired to take advantage of them.

Initial Challenges

ACP approached the industry vendor group the Electronic Health Record Association (EHRA) shortly after CMS made their announcement with the goal of getting vendor buy-in to support the changes. It became apparent fairly quickly that electronic health record (EHR) vendors were already on the path of supporting the changes with functional changes and some already had tools in the software that met the regulations. Talks then turned to publishing a whitepaper or a ‘Best Practices’ document. Not the most exciting or inspiring stuff.

As the chair of the Clinician Experience Workgroup at EHRA, I began discussions with ACP’s Physician Champions to better understand the problem. A few themes emerged:

- The E/M Coding changes that AMA recommended were already inline with what was considered best practices for clinical documentation both in research and by vendors.

- Physicians were having a difficult time writing ‘good, useful, compliant’ notes, even under previous regulatory standards.

- A major block to writing shorter more effective clinical notes was confusion about what was required and physicians defaulted to putting everything in their note to avoid any risk.

🚨 Major insight alert 🚨 we were about to write another list of best practices for a group of people who were too confused and burdened to even care about the last set of best practices. We had to make something that would break the mold and help people break out of a rut.

A Productive Workshop

Once we uncovered the true lay of the land, ACP representatives were open to my suggestions of focusing on design process that would build consensus across a variety of voices, focus our outcomes on real word actions, and allow us to move very quickly. The last factor was important as we were already in December of 2020 — the CMS changes would take effect on January 1st! A discussion across the many stakeholders who would be affected by the regulatory changes seemed appropriate, but it needed to produce more than just talk.

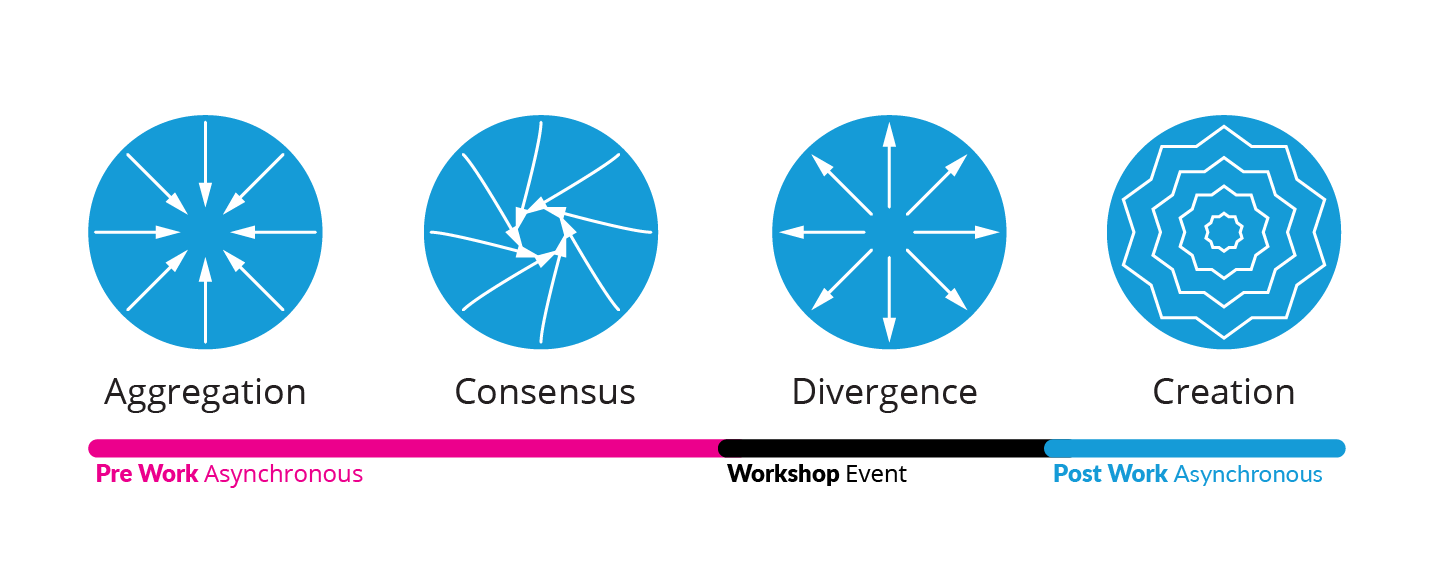

I proposed a workshop that would focus on educating physicians about what a good note looks like in 2021 with the updated billing guidance. The deliverable would be one-page tip sheets that could be handed directly to physicians at their place of practice. I set about creating a collaborative workshop with four phases:

- Aggregation Using contacts from EHRA member companies, the ACP, the AMA and other industry groups we collected an extensive list of interpretations to the CMS regulatory changes. These were coded into language that would impact clinical documentation, language that felt poorly defined and needed more clarification from AMA/CMS, and language that might create more clinical burden. Building this library of commentary and interpretation allowed us to quickly suss out how confident a large chunk of healthcare actors felt about the coming rules. We utilized transparent, shared documents to foster conversation when there were disagreements between stakeholders.

- Consensus The core ‘State of The Note’ team synthesized the various commentaries into a list of agreed upon impacts and common questions. Fortunately, there were very few outliers in interpreting the rules and the primary outcome of this step was to bolster any recommendations we might make.

- Divergence For the actual workshop we recruited practicing physicians from Primary Care and Orthopedics, along with representatives from various clinician and regulatory groups including ACP, AMA, APA, CMS, as well as representatives from EHR vendors. These participants were broken out into groups with a clinical note that was realistic, but far from good or useful. Each group was tasked with editing the note to better fit the new reality with CMS updates. Each group focused on either a primary care or orthopedic note, and presented their outcome at the end of the workshop.

- Creation Armed with the new ‘good’ notes each team had created, as well as the copious notes from the discussion that led to each deliverable, I set about creating exemplary notes and guidance for clinical documentation. I worked with representatives from the workshop to refine the designs.

Visuals to Inspire

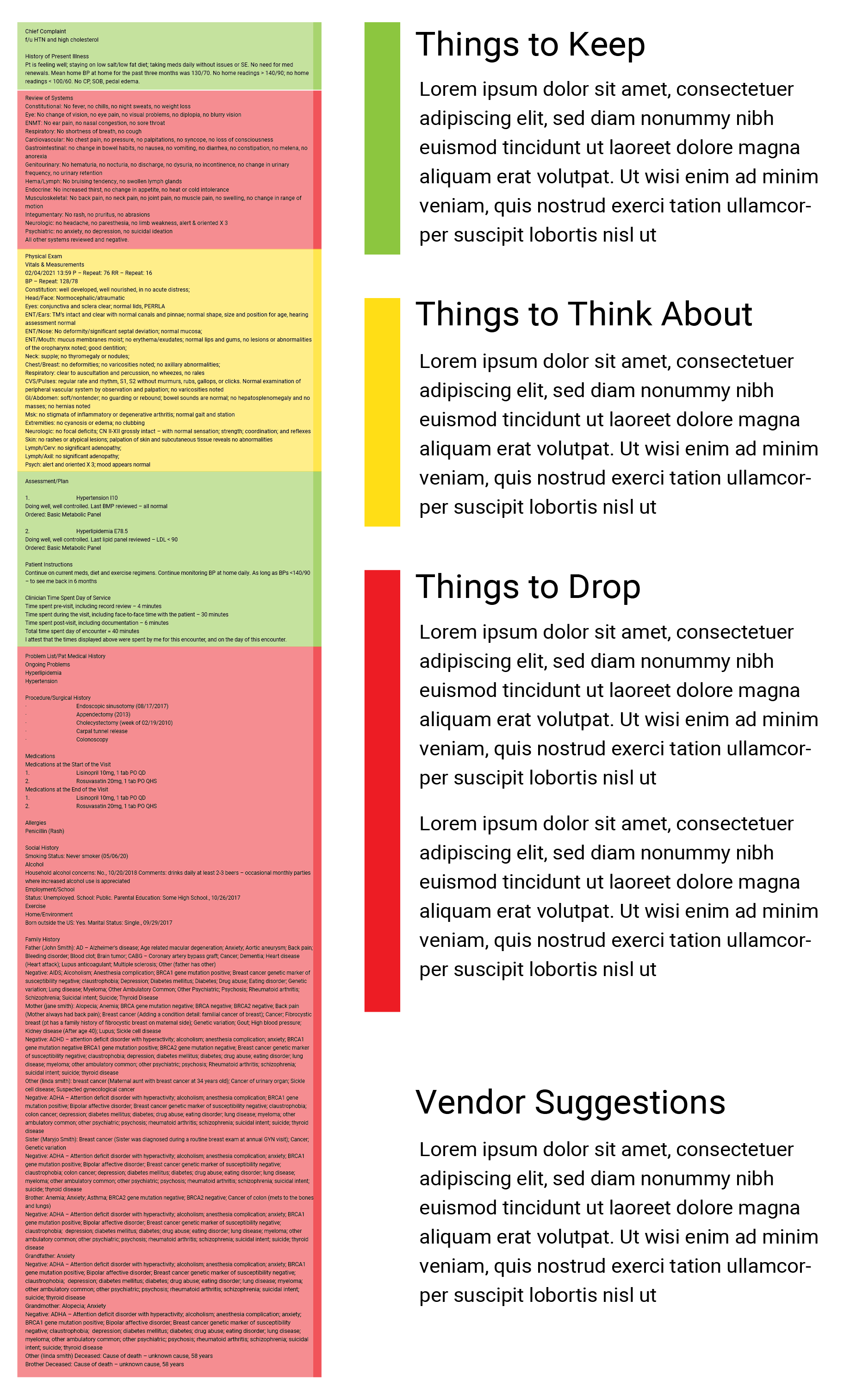

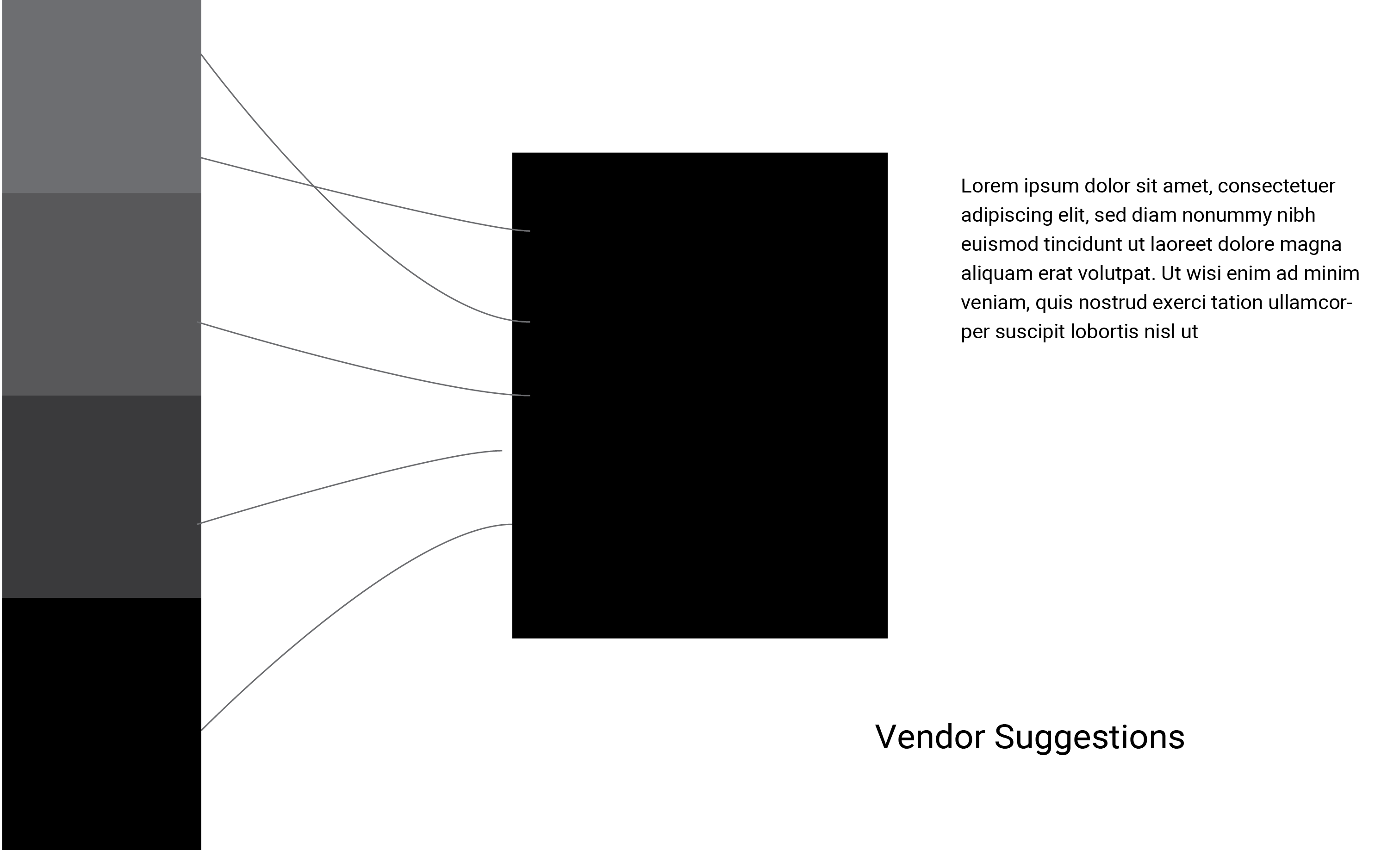

As I looked over the good notes, I was struck by how short and easy to read they were. An essential visual element was highlighting the brevity of a good note. In addition, the discussion from each group focused on the fact that no information was lost with a more concise note thanks to EHR technology. I knew I wanted the poster to fit on one sheet of paper, and still look good at poster size, as well as be able to be printed in black and white.

I played with a number of different layouts, trying to keep both the bad and good note somewhat legible and clear. It was pretty noisey and presented serious challenges to fitting on a letter-sized print out.

Stakeholders, especially physicians, dismissed the idea that the bad lengthy note needed to be read in detail, “doctors know what a bad note looks like, they’ll recognize that.” Instead, they encouraged making the good note be prominent as a way to entice doctors to look more closely. In addition, they felt strongly that the color coding concept — that some things should stay, some things were more nuanced, and some had to go — would best encapsulate the complexity of the issue. With that feedback in mind, I thought about Sankey visualizations and their capability of showing inter-relationships and ‘movement’ between data. Stakeholders loved the way it clarified that “all the data is still there, just place more intelligently.”

Outcomes

This was one of the most effective conversations I’ve had about healthcare policy, and how it will impact my doctors every day. Great discussion, great insights, and I’ll use this tip sheet in my clinics.

– CMIO

Our stakeholders and ACP leadership were very pleased with our output and the collaborative spirit in which it was created. The event happened within months of multiple other discussions about clinical burden, and avoided the pitfall of those events by producing something targeted, actionable, and applicable to current behavior.

One thing I would have changed: we should have had a more sophisticated rollout of the materials. We went through the standard communication process for ACP and EHRA, and while effective, I do not think we had the immediate impact we should have. People are using the tip sheets, but I still come across healthcare groups that are struggling with clinical documentation who have not encountered them. One hypothesis I have is that we lost a bit of ‘buzz’ due to the workshop being virtual. It required less effort to participate in and therefore fell into participants’ stew of virtual meeting memories. Without the urgency of an in-person workshop, they felt less ownership of the final outcome and did not feel as compelled to share out the story.